Making sense

From genetically modified foods and the MMR vaccine to more recent conspiracy theories about Covid-19 and 5G masts, it can be difficult to communicate legitimate scientific evidence to the public.

In a world where misinformation and misinterpretation of evidence can easily proliferate, how do you help the public scrutinise and interpret the outcomes of scientific study accurately?

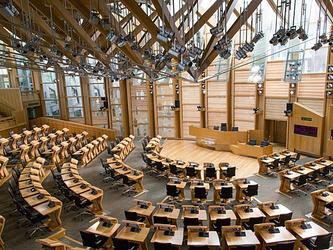

Sense about Science aims to make science – and evidence more generally – more accessible to the public, politicians and journalists, and correct some of the misconceptions that arise. Since its creation in 2001, the organisation has spearheaded several successful strategies to improve understanding of evidence, from ‘evidence week’, which has run in the UK parliament since 2018, to the AllTrials campaign to publish the results of all clinical trials.

“Over the past two decades, we have become more focused on system change, and thinking about the capacity within particular systems – whether that is parliament, the media or community organisations – to engage critically with evidence, and looking at how well-equipped they are with the right questions and insights they need,” says Tracey Brown, director of Sense about Science.

“What has stayed with us from those early days is that we always started with the real questions people had, rather than the story researchers want to tell. Whereas researchers might think about how they want to put their work across to society, we have always started with questions such as ‘should I be worried about the phone mast at the end of my garden?’, and unpacking that. Our term for it is ‘public led, expert fed’.”

Sense about Science works with organisations, including the government, parliamentarians, the media and researchers, to help them ask the right questions or present findings in ways that ease interpretation. For example, ‘evidence week’ emerged from a desire to help MPs analyse the impact of technical legislation, while recognising the range of other issues they have to deal with on a daily basis, Brown explains.

“MPs can be dealing with 40 problems a day in parliament and constituencies, and you need to turn from discussions about innovation to, perhaps, one on drone noise – it’s the same with journalists,” she says. “How does the insight community equip them better with the research, knowledge and resources they need to ask the right questions and scrutinise the evidence?”

The pandemic has heightened the importance of communicating accurate information, with the relative lack of knowledge about the virus meaning conspiracy theories have circulated, and speculation about the disease has been reported in the media and discussed online. However, Brown feels it has also opened up opportunities to educate people on research and evidence, offering a real-time demonstration of how the research-gathering process works.

“For those of us looking to equip people with a better understanding of evidence and the right questions to ask, that has opened up enormously. I am very glad it has opened up around modelling and data science, as this is a field that has had little public, policy and media scrutiny, and yet is advancing rapidly in areas of major decision-making in society.”

However, she is critical of how some of the policies implemented to stop the spread of coronavirus have been communicated to the public, with a lack of discussion about their context leaving people to read between the lines when interpreting official guidance.

“There was a lack of understanding of just how much communication there needed to be about the way that evidence is used in decisions,” Brown says. “The crisis isn’t just the disease spreading – the crisis is also how people are reacting to and understanding it.”

She is also sceptical that measures to remove conspiracy stories from social media platforms will have the desired effect. Ofcom research on news consumption found that, in early April, half of people were seeing misleading information about the virus on a weekly basis. Brown warns that simply removing misinformation does not adequately solve the issue.

“People do not achieve engagement and trust by shutting down their opponents,” she says. “If you want to get rid of misinformation, you need to think about what you put in its place and how you equip people with the right questions that help navigate the evidence.”

One of Brown’s biggest frustrations, more generally, is the lack of engagement from researchers in how their work is promoted – particularly in the early stages of a project – which can risk the end results being misused in wider debates happening across society. To counter this, Sense about Science works with research teams on projects of potentially major public interest and helps them to run engagement programmes about their findings.

“I think the research community thinks about public engagement as the thing you do once you have finished your project, rather than a conversation you begin earlier,” she says. “It astonishes me how researchers can just release information. Researchers will say that their work has been massively misinterpreted and really polarised, and you think ‘they must have looked around them at the debate that this research was going into and seen there was a hunger for stories of that nature’.

“Now is the time to think a lot more about what kind of questions you would want people to ask, and engaging the world more in the research question rather than the research answer.”

This article was first published in the October 2020 issue of Impact.

We hope you enjoyed this article.

Research Live is published by MRS.

The Market Research Society (MRS) exists to promote and protect the research sector, showcasing how research delivers impact for businesses and government.

Members of MRS enjoy many benefits including tailoured policy guidance, discounts on training and conferences, and access to member-only content.

For example, there's an archive of winning case studies from over a decade of MRS Awards.

Find out more about the benefits of joining MRS here.

0 Comments