The research industry needs refriction

The industry demands ‘insight’

As workers in the qualitative research industry, our purported prime directive is to develop an understanding of people – to see them as holistically as possible, to figure out what makes them tick, to help our clients see them not as dollar signs, but as human beings. The unspoken and unattractive truth, however, is that people are messy.

Life is complicated, and the humans who move about in this world are subject to many forces beyond their control. They must endure the endless indignities and discomforts of this earthly existence. They aren’t always their best selves. And curiously, it can feel like that real-life messiness surprisingly doesn’t always have much of a home in this work.

Rather, it can feel like the actual job of a qualitative market researcher is to deliver insights that are perfectly smooth and sanitised… to sand off the rough edges of what we see and hear, and package it into a tidy, palatable deliverable. One whose narrative isn’t too complicated, that doesn’t need too much time or effort to digest. A message the leadership can absorb in (literally) two minutes.

‘Our kind’ of people

Developing palatable insights begins in the earliest stages of a research project, when seeking out the ‘right’ kinds of people to talk to. Usually, this means seeking out urbane, educated city-dwellers who make good money and don’t have off-colour or unprogressive views – people who more or less represent the segment or profile and who are specifically selected to fit neatly within existing boxes.

While many clients claim to want a ‘real’ view of humanity, that desire comes into conflict with a deeper desire for simplicity and comfort. This isn’t just political discomfort being avoided, it’s also human discomfort. In recent memory, a fashion brand asked a participant to be excluded from the research because they had cancer.

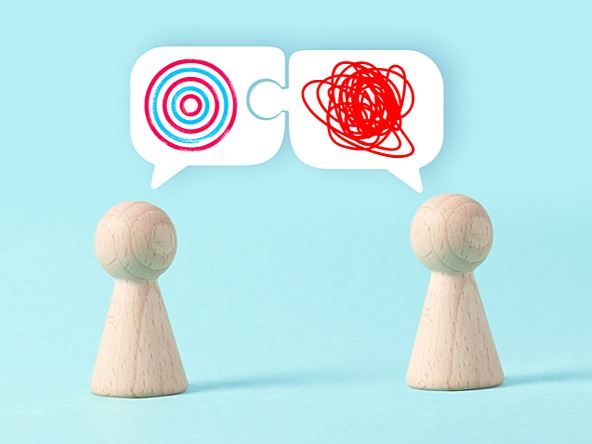

What this ultimately boils down to, sometimes, is an unconscious desire to cultivate and reinforce a completely frictionless reality – one in which the identities, stories, and motivations are clean and two-dimensional. This results in a shallow, frictionless market research world where brands are made to seem important and but nothing messy and actually important is.

The world we live in

This is not a problem unique to market research. In a world where we have so little control, yet so much information at hand, this desire for streamlined, uncomplicated realities makes intuitive sense. Smoothing out one’s entire existence has never been easier, or more culturally encouraged. The algorithms that shape much of our lives exclusively feed us content that either resonates with us or caricaturises our fears (while the truth lies somewhere in the middle), but rarely are we presented with thoughts that challenge our worldview in a way that’s meaningful.

When we talk about undesirables or radicals or kooks, it’s easy to lose sight of the fact that we’re talking about people. If we are to believe that people are the results of the contexts in which they live and the systems that surround them – that must be true of everyone.

We are at risk of choosing a convenient truth over an honest one because we’re uncomfortable discussing half or more of any given population, an especially egregious state of affairs when we’re talking about research.

Good for the goose

Too often, people are wholesale dismissed because they appear to be on the outside of prevailing norms and mores, which is antithetical to research on a conceptual level. Good research means looking at the whole of a thing, not just half.

Engaging in truly agenda-less conversation means seeing people as they are, being there to understand them, and not needing them to be different. Listening doesn’t mean endorsing or condoning. It means trying to see someone in their wholeness, through good faith conversation.

The status quo is bad for business, to boot. Limited insight leads to limited success. Half-truths lead to half-cocked campaigns that may work for the people we speak with, but won’t reach beyond the pale. On the rare occasion a client is willing to get messy and let us truly dig in, we get to focus on the research instead of pruning the truth for a select audience in a single meeting.

Going beyond empathy

One thing I’ve learned in this line of work is that people generally make sense if you understand their life, how they got to this place in time, and what happened to them along the way. Their childhoods, the systems that worked for and against them, and the idiosyncrasies of their stories inform why they are the way they are.

This goes beyond empathy, the buzzword du jour. Instead, it’s about getting to know the workings of a mind without having to agree with it.

As researchers, it behooves us to get comfortable with discomfort. Engaging with people means sometimes coming into conflict, and that’s OK. It’s part of our work as both researchers and human beings. People need to feel safe with us – like they won’t be ridiculed or demeaned for their thoughts and feelings. That means listening to all of it, and trying to understand why.

If we, as researchers, can’t bear to engage with the friction, how can we expect that of others?

It is worth getting into the mess – to not only observe it, but to get close to it, to shake hands with it and to seek to truly understand. May we, as a field and as a species, be emboldened to push past the discomfort and get back into the friction.

Eve Ejsmont is a research director at Further & Further

We hope you enjoyed this article.

Research Live is published by MRS.

The Market Research Society (MRS) exists to promote and protect the research sector, showcasing how research delivers impact for businesses and government.

Members of MRS enjoy many benefits including tailoured policy guidance, discounts on training and conferences, and access to member-only content.

For example, there's an archive of winning case studies from over a decade of MRS Awards.

Find out more about the benefits of joining MRS here.

0 Comments