The myth of customer feedback

A few years ago, I interviewed a woman who’d just moved into a new-build house as part of an affordable housing scheme. On the surface, Annie seemed absolutely delighted with the place. She waxed lyrical about how much nicer it was than her previous area – “a drugs den” – and how grateful she was for the opportunity to have moved in.

I had a gnawing suspicion there was more going on than she was saying, so after 25 minutes of this ‘highly satisfied’ conversation, I asked her one last time if anything at all that hadn’t been perfect:

“Well, it’s a tiny bit inconvenient that the space to put in a dishwasher is too small, but I’m not moaning.”

“OK. Anything else?”

“Um… well, the driveway is a little small – I can’t open the doors of the car properly so can’t get my daughter out of the back seats. She has to climb into the front to get out.”

“Anything else?”

“Yeah, the stairway is missing a handrail at the top, so my daughter has fallen down the stairs twice and my husband four times.”

“Wow, OK. Anything else like that?”

“We did have a big brown patch appear in the ceiling, so someone came and opened the loft hatch and a load of brown water poured out. It ruined the carpet, so they replaced that too. They didn’t pin it down properly though, so my husband tripped over that and sprained his ankle.”

Then, her daughter appeared on screen, so I asked what her favourite part of the house was.

“Oh the garden, I love having a garden.”

To which Annie added:

“The garden is lovely. I mean, it does flood whenever it rains. But we’re so lucky just to live here.”

She gave a score of 10 out of 10 on her customer satisfaction survey.

This is the myth of customer feedback, one of the three myths that I believe get in the way of organisations creating a truly human experience, that I discuss in my new book, The Human Experience.

There’s never been more information about customers coming into organisations, driven by an epidemic of feedback requests that customers now live in. Not a single interaction with a company can go by without some kind of request for feedback on the experience.

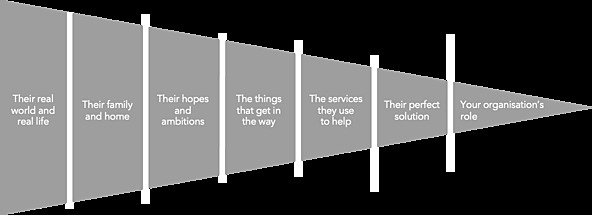

But if you think as a customer’s life as a wedge, at one end is all the things that matter to them: their family, home, job; hopes and ambitions; the things they enjoy doing, and the things that get in the way; then, the relationships they keep, the services they use to help, and finally, right at the end, the role each organisation plays, a tiny part of the overall picture.

Yet nearly all of this customer information coming into organisations is at the thin end of the wedge. What do you think about us? About our product? About our service? Would you recommend us?

Very little is at the thick end – understanding what really matters to customers in their lives, and how the organisations can be most useful to them.

This myth is a major problem in organisations for two reasons.

First, it worsens the customer experience, acting as the last moment and memory of an experience that is driven by the well-known ‘peak-end rule’ (where we all remember the most emotional moment of an experience, and how the experience ends).

Secondly, and crucially, this deluge of inside-out customer information convinces leaders they’re close to what matters to customers – whereas in truth, they’re only close to customers’ opinions of their business.

More than that, what they’re close to is the average opinion of their customers, creating an illusion of an experience that no one else is having. Would you rather know there’s an average wait time of five minutes, or that 10% of people wait more than half an hour?

So, whilst feedback surveys have an important role to play in understanding how customers feel about the transactions they make with organisations, to really understand customers – and trail-blaze on their behalf – it’s crucial to do more than just ask people a few questions.

You need to get to the thick end of the wedge and understand what really matters to them – starting with learning how big a dishwasher is.

John Sills is managing partner at The Foundation and author of The Human Experience

We hope you enjoyed this article.

Research Live is published by MRS.

The Market Research Society (MRS) exists to promote and protect the research sector, showcasing how research delivers impact for businesses and government.

Members of MRS enjoy many benefits including tailoured policy guidance, discounts on training and conferences, and access to member-only content.

For example, there's an archive of winning case studies from over a decade of MRS Awards.

Find out more about the benefits of joining MRS here.

0 Comments