Learning the why: Hearing customer stories

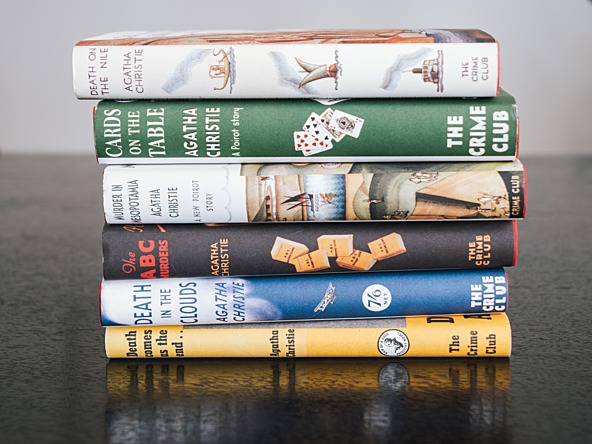

Modern detective stories often tackle a different puzzle to traditional ones. Agatha Christie’s stories were whodunnits. Today’s psychological thrillers might reveal the killer on page one, but explore a subtler question: they are whydunnits. Why did this person turn against their victim? What stresses, traumas, guilt or hidden desire made them a murderer?

UKTV felt there was untapped potential in their crime drama channel Alibi. It was delivering but, perhaps, lacking stab-through, and they had to find out why. The marketing team couldn’t solve the problem if they didn’t know what was causing it.

This is a common scenario. Digital metrics and sales data often provide early warning of what is happening in your market, but they hardly ever tell you why. It is the research team’s job to explain that, but the tools available are not always powerful at uncovering the reasons.

Surveys are good at spotting trends, if you track them over time. They can give insight into behaviour and attitudes, but they don’t provide a good way for respondents to articulate their reasons for changing behaviour.

Focus groups and depth interviews go deeper, but they still rely on interpreting claimed behaviour and rationalisations. In a world with more choice than ever before – from where to access TV shows though to what’s available to watch – it’s harder than ever for viewers to articulate what’s driving their behaviour. Probing and laddering get you only so far, before the respondent runs out of deeper reasons and resorts to “I just don’t like it”.

Therefore, UKTV were looking for a new approach. They discussed it with Irrational Agency. We looked for some inspiration in the crime shows on Alibi itself, and realised that many of them had one thing in common.

Every detective investigating a murder does one consistent thing. They talk to everyone involved and listen to their stories.

Stories are powerful at revealing the ‘why’. Every story ultimately is composed of a series of cause-and-effect events. A occurs, which causes B to happen, which causes C to take place. You may not know in advance whether it will end up at Q or Z, but in hindsight there is an inevitability about it: everything has a ‘why’. Why did C happen? Because B did. Why did B happen? Because of A.

Even if they don’t share the full facts with you, the witnesses and suspects inevitably reveal what they believe about ‘why’. The story they tell gives you a clue to their motivations, the triggers of their actions and the invisible barriers in their minds.

That’s just what UKTV needed to know. We collected stories about TV viewing and the crime genre from hundreds of Alibi viewers and representatives of the target audience. Reading through them, we turned ourselves into hybrids of detective and literary critic. Always looking for the subtext, the beliefs about the world that the stories revealed.

But it wasn’t all human judgement. We also analysed the connections in the text using automated grammar analysis, and gathered implicit word associations from the respondents using reaction-time-based tools.

Once we had our hypotheses of ‘why’ – our ‘whypotheses’ if you like – like a detective setting a trap, we tested them out. We created a second survey to measure how viewers would respond to specific images, assets and choices.

Ultimately we created a picture that told us what people really needed from their crime channels: thrill, intrigue and a twist. We got a true picture of how much difference the brand makes – seeing through the rational viewers who insisted they only care about the programme and not the channel.

UKTV shaped their marketing around these insights, and changed the way their research team tracked success for the brand – new attributes and new objectives. On the back of this campaign, Alibi achieved its highest viewing figures in five years, and saw a record-breaking new programme launch which delivered 1,400% of the viewing figures previously achieved in its time slot.

All of this was born out of listening to the stories our viewers told us, and taking them seriously – not literally.

What’s the ‘why’ of this story? Why am I telling you all this? Because our industry doesn’t always encourage respondents to tell stories. Sometimes we’d rather they just answered our questions instead of wandering off into anecdotes about their grandparents, the neighbours or their children’s school. We need to realise that’s where the gold is – not in the rationalised answers to a rating scale, but in the truth revealed by a narrative.

I’d like to see us move away from that old dichotomy of qual or quant. A third way is possible: encouraging respondents to open up with qualitative prompts and story-sharing, then analysing and distilling the results with quantitative help. It’s about much more than just text analysis: it’s about structured narrative research.

What are the narratives that explain why your consumers are, or aren’t, buying your product? What narratives could motivate them to change? Start by hearing their story before writing your own.

Leigh Caldwell is co-founder and partner at The Irrational Agency.

The Irrational Agency will be appearing at the Market Research Society (MRS) behavioural science summit on 29th September. For more information, please click here.

We hope you enjoyed this article.

Research Live is published by MRS.

The Market Research Society (MRS) exists to promote and protect the research sector, showcasing how research delivers impact for businesses and government.

Members of MRS enjoy many benefits including tailoured policy guidance, discounts on training and conferences, and access to member-only content.

For example, there's an archive of winning case studies from over a decade of MRS Awards.

Find out more about the benefits of joining MRS here.

0 Comments