FEATURE9 October 2012

All MRS websites use cookies to help us improve our services. Any data collected is anonymised. If you continue using this site without accepting cookies you may experience some performance issues. Read about our cookies here.

FEATURE9 October 2012

People have always let themselves be seduced by advertising, but social media now makes it easy for them to tease and mislead brands. Simon Patterson, Alan Branthwaite and Jessica Neild call for an honest dialogue.

From time to time, the ethics of qualitative research and the ways in which its findings have been used by advertising agencies have been questioned. This was particularly true in the early days of Ernest Dichter ( 1907-1991 ), who laid the foundations for much of what constitutes modern qual research. He introduced depth interviews for exploring the needs and motivations of consumers, winning converts among the ad agency executives on Madison Avenue, who became known as the Depth Boys.

“Modern-day Vance Packards find themselves questioning the ethics of big companies who trawl social networking sites, unseen by consumers, looking for insights. Is this a violation of data privacy?”

From his interviews, which often lasted two hours or more, Dichter would come up with creative ideas to help advertisers relate their products to human emotions and motivations. Cars were objects of male potency, he said. He likened the convertible to a mistress and the sedan to a wife, and recommended the development of the coupé so that men could feel like they were having their cake and eating it too. He also inspired the Esso consumer with a campaign developed from his research which urged drivers to Put a Tiger in Your Tank.

Dichter gave objects new meanings in advertising. Lipsticks became phallic objects and the lips were a honey trap for men. And every woman dreamed of walking down Park Avenue in nothing but a Maidenform Bra. His research findings were hailed as a revelation – helping advertisers to understand and tap into consumers’ real needs and wants.

The public, if reluctant to admit it, were excited and fascinated by the change in consumer culture that this new marketing brought – the promise of products that were more interesting, more self-indulgent, more exciting and, importantly, more fun. This was one of the main driving forces behind the post-war boom in the US economy. It encouraged a desire for luxury goods and for people to replace the old with the new, even when the old was still serviceable.

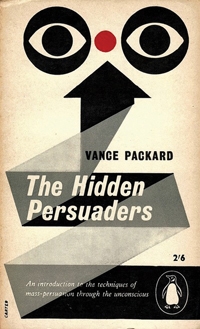

But the use of motivational research techniques by ad men was not without its critics of the ethics involved. In 1957 American journalist Vance Packard raised doubts about Dichter and the Depth Boys in his famous exposé The Hidden Persuaders. It sold over a million copies and was the top seller in non-fiction books for six consecutive weeks. He claimed that unethical advertisers were using hidden symbols to manipulate the unconscious mind, by “channelling our unthinking habits to influence our purchase decisions and our thought processes”.

But Packard was too late. The tide had turned and most consumers could not be forced back to more puritanical ways. They were enjoying the narcissism of being the centre of marketing attention and being seduced instead of sold to.

What is ethical in research and advertising depends on the way in which people perceive how they are being treated and whether they feel respected.

In contemporary qualitative research (including similar disciplines like ethnography) ethics are well integrated into professional practices. Interviews rely on an open dialogue between researchers and respondents. Only by taking an interest in and engaging with consumers, to get them to share their lives as collaborators and partners, can we fully explore their motivations, emotions, aspirations and desires, along with the pressures and influences that shape their decision-making.

However, concerns about the ethical treatment of consumers haven’t gone away. The most pressing issue today relates to social media channels like Facebook and Twitter and how researchers and advertisers use them to understand consumers. In some quarters, social media monitoring is considered a valid alternative to qual research, but unlike traditional qual there is rarely an open dialogue between the researcher and the researched.

The dialogue that takes place is between consumers – researchers and advertisers are merely listening in.

And so modern-day Vance Packards find themselves questioning the ethics of big companies who trawl social networking sites with cyberbots, unseen by users, looking for consumer insights. Is this a violation of data privacy or are participants willingly sharing their opinions and data with everyone, not just their friends and followers? Ethics aside, there are also questions about the validity and authenticity of social media data. Are consumers being selective in the types of information they are willing to share about themselves to outsiders?

A paper written by Peter Cooper and Simon Patterson in 2000 introduced the concept of The Trickster into the ethical debate about research and advertising. It explored how this ancient archetype works to seduce the consumer through marketing.

Unlike Packard, Cooper and Patterson recognised that consumers enter into a cooperative relationship of mutual consent with advertising, television programmes and other media. Consumers are not unwitting in their own seduction, but instead enter into a kind of game played between themselves and brands through the medium of advertising. The Trickster operates at a deep psychological level within the more primitive part of our minds, appealing to our wishes to be indulged and persuaded.

By using an array of devices to entice, convince and seduce, advertising dazzles consumers. They allow the id to have its way and play along with the Trickster who tickles our fancy. Consumers know that Esso will not actually put a tiger in their tank, and that Axe/Lynx will not give us Herculean pulling power. But these ads play to our desires, and consumers let them.

But in the social media sphere, is the joke on us? Are consumers now acting as Tricksters in their own way and turning the tables on researchers for their own amusement and self-indulgence? Are they adopting fantasised personas or playful identities online to tease and mislead brands?

Since Dichter’s time, marketers and consumers have engaged in a dance of mild deception, with each taking turns to lead. But the power to dissemble is now more in the hands of consumers thanks to social media. This is in serious danger of undermining the value and credibility of market research, by turning it into a game of charades. The industry’s response has been to issue guidelines for social media research, which stress that consumers should be willing participants in the research process. We welcome this. Research should be a democratic process in which respondents actively exchange ideas and reveal their thoughts and feelings. In doing so, we come to know them openly and honestly.

Only then can the dance of mild deception continue, with both parties – consumers and advertisers – on equal footing.

Simon Patterson, Alan Branthwaite and Jessica Neild are CEO, consultant director and associate director, respectively, of QRi Consulting

There was little love lost between Ernest Dichter and Vance Packard. The former was an Austrian-American psychologist who pioneered the business applications of Freudian psychoanalytic concepts and techniques, the latter an American journalist, social critic and author with a distaste for the rampant consumerism that Dichter helped advance.

In The Hidden Persuaders ( 1957 ) Packard compared the motivational research practised by Dichter to “the chilling world of George Orwell and his Big Brother” and railed against the influence and manipulation of consumers.

Three years later his book The Waste Makers lambasted companies for designing products to become obsolete after a period of time, so as to encourage people to buy more things.

But in Dichter’s view, Packard and similar critics were “morality hucksters” who, after ranting about consumerism, cashed in their royalty cheques and retreated “to their Connecticut homes to cool off with a drink iced from a refrigerator engineered by the waste makers”.

Brian Tarran

1 Comment

Chris Robinson

12 years ago

This is a very thought provoking article and the main point will I am sure be ignored by all those whose rose coloured glasses lead them to believe with incredible confidence that the whole SoLoMo area is the game changer for market research. The other consumer-related issue that has not been recognized is that social media is like TV in its earl;y days, no one could get enough of it. Well just think of TV now. We are already seeing the first signs of users closing off their social reach and actually reducing usage levels. There is also a move by mobile iusers to turn off location devices - so much for the immediacy of mobile surveys! A recent piece of research in the US indicated social media users were getting fed up with the one way sharing of information of companies collecting information online. My prediction is social media users will eventually start to close off the communications space to those things much more relevant and those people that are meaningful in their lives and that will not always include market research. The hubris of the industry, so enamoured with social media, is just amazing at the moment and I see only a few voices in the wilkderness challenging this belief. This article hopefully adds to the discourse.

Like Reply Report