In traditional research, the quotes taken from surveys, focus groups or interview results can never be associated with individual people because there are no names attached to the verbatims. As researchers, we pride ourselves on the anonymity we provide our research participants because it allows them to be completely open and honest with us. But when it comes to social media research results, it’s a completely different story. Any verbatims that are pulled from social media and copied directly into a research report can be easily traced back to the original author.

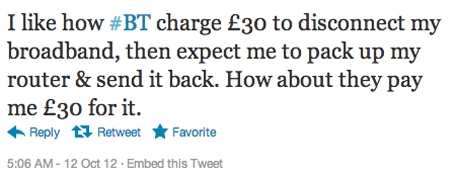

At the recent IJMR Research Methods Forum held in London, I shared just such an example with the audience – so let me share that story with you now. It started with a research project about BT, a telecoms service provider. In the research report, a verbatim was copied directly, without any masking, and without any individual attribution, from social media. It simply stated:

“I like how #BT charge £30 to disconnect my broadband, then expect me to pack up my router & send it back. How about they pay me £30 for it.”

The client saw that verbatim and wanted to know more about the person who made the comment. Actually, they wanted to talk directly with the person and see if they could convince them that what the brand was doing made sense. They decided to spend a few minutes on an internet search to learn more about this person. Given that the verbatim was succinct and detailed, they suspected it was a tweet so they went directly to Twitter.

After typing a portion of the verbatim into the Twitter search box, they were delighted to see the result.

In just a couple of seconds, they had found the original author. They now had a man’s username, his first and last name, as well as a user photo. With those three details, they knew it would be easy to find out even more about this person.

They took the man’s name and switched over to Facebook to run a quick search on his name. Though many people had the exact same name, only one user photo matched the Twitter photo. In fact, it matched right down to the red and blue checkered shirt. They had found the right person. In less than five minutes.

This man’s Facebook photo showed him wielding a machine gun. Red flag number one right there. This is someone they probably should be careful dealing with should they finally decide to contact him directly. Reading through the rest of his Facebook page, they noted the man’s birthday, where he had gone to college, where he currently resided, the names of his cousins and sister-in-law, and that he was married. Pity the poor woman.

Not much else of interest was to be found on the rest of this man’s Facebook page so they continued on with the next best thing. And that meant perusing the Facebook page of the man’s wife. There, lo and behold, they found a virtual gold mine. There was treasure trove of baby photos. They traced the genders, ages and names of two very cute, vulnerable and precious little babies that hadn’t been shared on the man’s own Facebook page. It made the client nervous that this gun-toting individual was responsible for the care of two innocent lives. The decided not to dig further.

Coming clean

So what’s real and what’s not real about this story? Well, the tweet was real, the stalking was real and the poor disparaged person was real – it’s Brian Tarran, the editor of this site. Brian gave me permission to stalk him and he even shared a real complaint for me to hunt down. The client wasn’t real, though, and there was no research report.

But the lesson to take from this is that this kind of stalking isn’t appropriate. Industry guidelines forbid it and require verbatims to be masked. If Brian really wanted a brand to find out about his wife, children, family members, work history and more, he would have taken it upon himself to tell them directly. A well masked verbatim from a socially responsible research company would have protected Brian from this intrusive behaviour. It would have ensured that Brian’s wife and his sweet little babies weren’t brought into the mess.

And no-one would ever have found out that Brian likes to play wargames at the weekend.

Annie Pettit, PhD is vice president, research standards at Research Now and chief research officer of Conversition Strategies. She is editor in chief of the MRIA’s Vue magazine, tweets @LoveStats, writes the LoveStats marketing research blog, and is the author of The Listen Lady, a novel about social media research.

5 Comments

Anon

12 years ago

"Given that the verbatim was succinct and detailed, they suspected it was a tweet so they went directly to Twitter." The hashtag next to 'BT' didn't give them a clue, then?

Like Reply Report

Anon

12 years ago

erm - he tweeted #BT not really trying to stay anonymous was he? or protect himself from BT's notice? surely the point of your story (if it were true) is that companies the size of BT should have internal staff full time monitoring and responding to consumers out there on public social media - and where does that leave the role of researchers? Plus: Dear Consumer: learn to use your FB privacy settings!

Like Reply Report

Anon

12 years ago

oh, and you don't have to go to twitter to search on twitter. just google the verbatim (or any bit of text)!

Like Reply Report

Jeremy Hollow

12 years ago

Hi Annie Great example, thanks for bringing this to life. I think you've highlighted a big question that needs some serious thought. When can a comment made in social media be taken as coming from a position of informed consent? In your example the use of #BT suggest a desire for a response or interaction from the brand. Where does this leave us as researchers? If we can be certain of informed consent, should we act as a bridge between brands and consumers? Jeremy

Like Reply Report

giulia baldi

12 years ago

The issues of anonymity and privacy surely exist in relation to SM research, but... people can be concerned of what use is made of their clearly private content (gmail emails and the likes), and feel the need of protecting some personal interactions and memories (learning SM settings) yet they definitely *love* to be detected when publicly talking about a brand on twitter... And we all know it, I agree. So why are we here discussing? Well, because the article seemed to forget it.

Like Reply Report