FEATURE28 May 2012

All MRS websites use cookies to help us improve our services. Any data collected is anonymised. If you continue using this site without accepting cookies you may experience some performance issues. Read about our cookies here.

FEATURE28 May 2012

…I’m younger than that now. The Big Window’s Lisa Edgar and the BBC’s David Bunker reflect on the gap between actual and perceived age.

How old are you? A fairly straightforward question, it seems, but for most people age is about more than their date of birth. It’s about how old they feel, how old they think they look, their mental age and other factors.

Age is the most commonly used sampling and targeting variable in research and marketing. “But how well does age really bind people together?” asks Lisa Edgar, founder of research consultancy The Big Window. “Marketeers and researchers love age because it’s simple, it’s linear, it’s quantitative, it’s sequential. But if we’re using it for marketing purposes it’s got to mean something to the people we’re marketing to.” In using age as a targeting variable researchers and marketers assume all people of the same age are likely to be similar in attitude or behaviour, or that they at least share enough in the way of similarities to be grouped sensibly together.

Anecdotally, we all know that this isn’t the case. Age is used as a rule of thumb, says Edgar, but she went looking for a better one, one that takes into account how old people consider themselves rather than how old they technically are.

She teamed up with the BBC, which had recently published a report – Serving All Ages – on the topic of age and how young and old people are portrayed in the media. James Holden, director of BBC Audiences, says: “We are constantly looking for ways to build on our understanding of all audiences and were attracted to the innovative nature of this project as it questions basic assumptions that the market research community takes for granted.”

Together, Edgar and BBC Audiences explored the idea of not only understanding and measuring the difference between actual and perceived age, but whether it could be modelled. Edgar worked directly with BBC Audiences’ head of research David Bunker. The challenge they set themselves was to develop a model that was more effective than actual age at predicting consumers’ preferences and behaviours. They also wanted to know if the model could predict perceived ages from commonly used profiling variables.

Birth of an idea

The starting point for the work was the development of a ten-item battery of questions that could be put to a sub-sample of the BBC’s Pulse panel to tease out respondents’ perceived ages. “The questions we asked were things to do with looks, behaviours, feelings, physical energy and mental energy,” says Edgar. “We really looked to stretch the concept out in every way possible to see what hung together and to see where there were patterns in the data.” There were two waves of research in total – both involving 3,000 respondents.

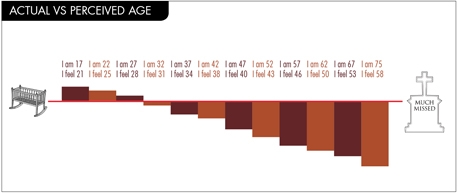

What the research showed was that in general people feel younger than they actually are. This was to be expected, but what surprised both Edgar and Bunker was the extent of the gap between actual age and perceived age. The chart below (click to enlarge) shows that people typically feel slightly older than they are until they hit 30. After that they start to feel younger – and then increasingly so. By the time they reach their early 70s, consumers actually feel in their mid- to late-50s. Subsequent analysis of both waves of the study suggest that as people approach their mid-70s the gap between perceived age and actual age starts to lessen – possibly as physical and mental health-related problems emerge.

With perceived age nailed down, Edgar and Bunker were able to link this information to the wealth of media-usage data that Pulse collects every day. “It’s our feedback panel,” says Bunker, describing how 20,000 panellists are asked to log in and record what they watched on TV the night before and how they feel about it. “We’ve got absolutely tons of data on real consumption.”

Using this data, Edgar and Bunker and colleagues set to work determining which programmes appealed to which age groups, and whether their audiences could be described as young or old at heart, according to their perceived age profile.

The team took some well-known programmes and TV personalities and mapped them by actual age and perceived age. Broadly, the research found that programmes such as US animation, those dominated by ‘young at heart’ characters and those with a strong celebrity or reality focus tended to sit below the ‘perceived age line’, regardless of the viewer’s actual age. On the other hand, programmes dealing more with real-life topics, tackling subjects such as death, marriage, losing weight or even the experience of fighting in a war, tended to sit above the perceived age line.

The research also pointed to a sweet spot for big shows on the mainstream channels – programmes such as EastEnders, I’m a Celebrity, Doctor Who, The X Factor and Harry Hill. These tend to appeal to people who, on balance, feel younger at heart – perhaps reflecting the fact that TV in general has a ‘younger at heart’ appeal, whatever the actual ages of the audience. Going with this grain is therefore more

likely to generate large audiences for a show.

Putting perceived age to work

Programme makers have long known that certain shows appeal to different age groups – Barb ratings bear that out. The value of perceived age, says Bunker, is in working out which shows appeal to those who feel either younger or older than their actual age.

“It’s early days,” Bunker says, “but if we can establish for everyone on our panel what their perceived age is we can then talk to programme makers not only about the audience they’ve actually got – as in their chronological age – we can also tell them about their audience’s perceived age. It opens up a whole other level of complexity and interest for them.”

Of the potential applications, Bunker points to scheduling and the trailing of new programmes as areas where perceived age could be of use. It might be that programmes that have similar perceived-age appeals could be placed together in the schedules, with relevant trailers threaded around them, or it could be about making schedules more complementary to what is on other channels. Bunker explains: “A good example is the recent series Titanic. Schedulers will say, ‘Right, Titanic’s on Sunday night, nine o’clock, who’s going to watch that? It’s

going to be people of this type of age, so what do we put against it on another channel that appeals to people of a

different chronological age?’

“With perceived age,” he says, “you then have the potential to look at what programmes might appeal to the anti-Titanic audience, people who may well be of a similar chronological age to the Titanic audience but who are more young at heart, say. It allows you to be more sophisticated in your scheduling.

“BBC Three is another good example of how this could work. At the moment they target 16-34-year-olds but using perceived age you can see there’s a further four million people, say, who are aged between 35 and 55 who feel like the target age.”

Bunker says: “I just know that we can apply this in lots of different ways but what we’ve got to do is go from a relatively small- scale pilot to asking everybody on our panel the questions we need to figure out their perceived age.” That work is now under way, albeit with a slimmed-down battery of items which Edgar and her team have found to be most predictive of perceived age.

“These include questions to do with internal age, so how old they think and feel; questions to do with external age, so how old they think they look; and then squashed in the middle is the third factor which is questions to do with the people they relate to or identify with, who they

mix with – a person’s social age, if you like,” says Edgar.

Meanwhile, she says, The Big Window is looking to develop age perception models that are sector- or brand-specific. The travel industry, for instance, might want a model that leans more towards the social aspects of perceived age, whereas the cosmetics industry would have more interest in the physical factors the affect perceived age.

She accepts it may be a struggle to wean marketers and researchers off their reliance on chronological age – but she’s happy to make the effort. “It’s about challenging what we do because, frankly, research is potentially wasteful if it doesn’t do that,” she says.

Lisa Edgar is founder of The Big Window and David Bunker is head of research for BBC Audiences

0 Comments