Given the power of these macro trends, I wanted to see what parallels there were for brands in the 1970s (and to a lesser extent the 1930s) when the UK was last at this point in the cycle. As it turns out there are quite a few similarities – and I think there is a lot we can all learn from them.

I was a teenager in the 1970s. I have vivid memories of not only the hardships of the times (including having to do my homework by candle light) but also the massive changes that took place in British society which have echoed through to the present day.

For those of you less familiar with the period, let me summarise the key similarities between then and now:

- Both saw enhanced public spending followed by cuts.

- Inflation increased.

- Purchasing power declined as wages did not keep up with inflation.

- Real interest rates (after inflation) were negative. In other words, savers lose out.

- There were credit booms which resulted in asset bubbles – including housing. These were followed by periods of deleveraging.

- Both periods suffered economic shocks from increased energy prices.

- Furthermore, these pressures were increased by the declining value of the pound.

- Both witnessed the destruction and disintermediation of jobs (in manual sectors in the 1970s and service sectors in the 2010s) with resultant rises in unemployment.

- Strikes increased, especially within the public sector.

- Many corporates had big cash reserves and did not want to invest because of continuing economic uncertainty.

- Perceptions of big business in general were negative. In the 1970s this was prompted by management’s attitude to the strikes; currently, the banking industry is held to blame.

- The world’s biggest economy (the USA) was suffering from increased debts – primarily due to the costs of drawn-out wars.

Of course, there are also differences between then and now – not least the currently higher average prosperity, the impact of technology and the internet. However the number of parallels is surprising, and some of them have direct implications for brands.

I have grouped these parallels into four categories: the challenge of inflation, how to live with austerity, the opportunity of change and the need to be positive. I’ll tackle each individually over the next several weeks, but let’s start with inflation.

The challenge of inflation

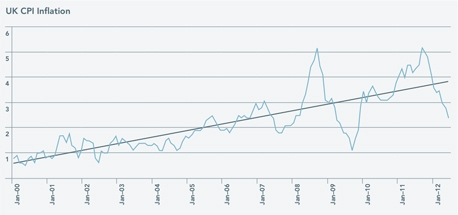

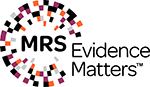

Over the last few years, the Bank of England has frequently insisted that inflation will soon return to below 2%. I disagree. Personally, I think there are few signs of this when you look at the actual data (see chart below). We are seeing inflation come down temporarily (currently 2.8% in June 2012 ) due to the recession, and VAT and fuel rises falling out of the index, but the overall trend still remains upwards. Indeed, many economists are speculating that it is unofficial policy to keep inflation high over the next decade to erode the value of government (and household mortgage) debts to more affordable levels.

Click image for larger version

The need for inflation education

So if I’m right, what implications will increased inflation have on brands and marketing? The first is that a generation of marketers have had little opportunity to work out how to deal with inflation. Those who joined the workforce in the last 20 years will not have seen inflation as high as it is today (let alone the 25%+ it reached in the 1970s). Those companies that are educating their staff in a new ‘high-inflation’ mindset will reap strategic benefits.

Here’s an example of how thinking on inflation needs to reflect our current situation: at the moment, many marketers hold off too long before passing on price increases, and then may be prepared to sacrifice margin for fear of losing share to competitors, who have yet to raise prices. The process is made worse by retailers also squeezing them on margin and demanding promotional offers. Indeed we’ve already seen examples of people getting this wrong. Last year, Carrefour (in France) passed across large price increases ahead of the competition and then suffered a big decline in sales.

The complexity of inflation

The situation is also more difficult and complex now than it was in the 1970s. As I discussed in my first Comley Report (the My Price trend), the power to dictate price is now more in the hands of consumers than it ever was. What’s more, history has shown that inflation has a different impact on different brands and sectors.

Increasing costs have a much bigger impact on some sectors (e.g. commodity users like airlines) than others (e.g. pharmaceutical providers whose costs are largely upfront and unaffected by inflation). In addition there is a key distinction in whether industries are able to pass on cost increases or not. Clearly some can. Indeed those in monopoly or semi-monopoly positions (like utilities) can even exploit inflation with above-average increases to make even larger profits. However others, where competition is rife, risk being sucked into a downward spiral of margin cutting until businesses go broke or decide to leave the market (as Spillers decided to do in the bread market in the 1970s for example).

Value not price

Lastly, inflation challenges brands to look for other ways to communicate value beyond just price. In particular, I believe customer service will come more to the fore as a key component of ‘value’. This is particularly the case in, though not confined to, the retail sector. An obvious example is the John Lewis Partnership which has recently demonstrated the impact of great customer service. They were one of the few retailers that saw year-on-year growth in the last quarter of 2011.

0 Comments